Netflix’s “The Outsider” Presents a Redundant White Savior Narrative

Netflix’s The Outsider places the White Savior trope front-and-center, amounting to another insensitive and tone-deaf portrayal of Asians and Asian culture. Jared Leto stars as Nick Lowell, a former American soldier who rises through the ranks of a Japanese yakuza clan despite his status as a gaijin (foreigner) in post-World War II Osaka.

This particular plot device – of a white man coming out of nowhere to lead non-whites – will be unfortunately familiar to anyone who has watched Tom Cruise in The Last Samurai (2003), Clint Eastwood in Gran Torino (2008), or Netflix’s Iron Fist (2017). To make matters worse, the film also indulges in stereotypical portrayals of East Asian women as being sexually submissive to white men and an Orientalized view of Japanese culture.

Enter the White Saviour

In The White Savior Film: Content, Critics, and Consumption (2014), sociologist Matthew W. Hughey argued that the white saviour trope “enables an interpretation of nonwhite characters and culture as essentially broken, marginalized, and pathological, while whites can emerge as messianic characters that can easily fix the nonwhite pariah with their superior moral and mental abilities.” The film’s main cast are all members of the criminal underworld, so everyone is playing a morally ambiguous character. Nick is thus not a virtuous and morally superior character by mainstream norms. The audience learns that he has a troubled past in the American military when he encounters a former colleague (who he quickly murders).

In the world of the yakuza, mafia, and other criminal subcultures, loyalty to one’s “family” is the primary virtue. Naturally, Nick is depicted as being a beacon of loyalty. He gains entry to the Shiromatsu family, a yakuza clan based in Osaka, after saving Kiyoshi’s life in prison and helping him to escape.

From then on, it is up to Nick to prove his allegiance and utility to his newfound family. His first task is to convince American manufacturer Anthony Panetti to provide more favorable terms to the Shiromatsus. Panetti breezily dismisses Nick’s request with a slew of anti-Japanese racial slurs:

“Look I’m sure you got respect for these people because they wear silk pajamas and bow like you’re the fuckin sun god when they pour the coffee. Frankly, I don’t give a shit about their rules or their traditions or whatever the fuck it is that you’re trying to explain to me. We won. Now what’s the point of winning a war if now you gotta worry about stepping on Japs’ toes? Now I don’t know if you’re banging some slanty-eyed broad and you’re getting all gooked out and sympathetic, but that’s the way it is.”

In return, Nick bashes his head in with a typewriter and begins his ascent up the ranks of the Shiromatsu clan. The scene seems to imply that Nick (and the film) is set apart from Panetti’s overt racism and xenophobia, but Nick’s characterization as a silent white savior enforces another manifestation of white dominance.

The film makes the subconscious equation of whiteness with rightness. Orochi, the show’s primary antagonist, is depicted as being opposed to Nick’s place in the yakuza family early on. With Kiyoshi’s help, Nick convinces clan leader Akihiro to formally accept him into the fold via a symbolic tea ceremony: “You have no family. You have no home. You are a stray dog. But today you may have a home.”

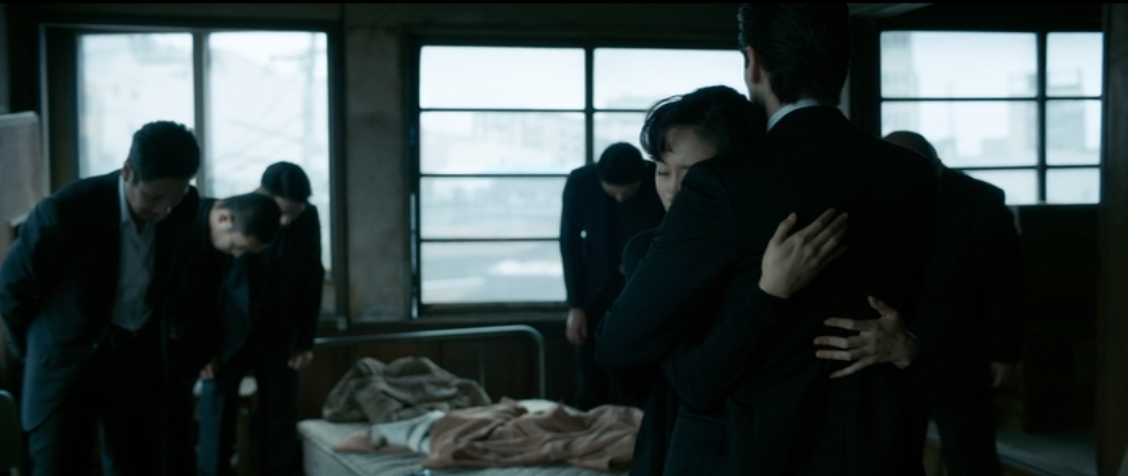

As Nick continuously proves his loyalty to the Shiromatsus, Orochi’s character arc moves in the opposite direction. Towards the end of the film, Kiyoshi, Akihiro and Nick find out that one-fifth of the clan – Orochi included – have defected to join the ranks of their arch-rival, a Kobe-based yakuza clan. During the climactic confrontation between the two warring clans, Orochi literally backstabs Akihiro after the distraught clan leader offers him one last opportunity to change his treacherous ways: “Orochi. You are my son. It’s not too late. Come back.”

This betrayal occurs after Nick had already saved Akihiro from being strangled by another traitorous subordinate. With Kiyoshi dead, it is up to Nick to take up the mantle of heroism. He does not actually lead the remaining Shiromatsu members into victory, but he does manage to brazenly walk into the rival clan’s meeting (with a limp from a prior gunshot wood), decapitate Orochi, and leave the premises unscathed.

He then returns safely to Miyu (Kiyoshi’s sister), who is now pregnant with his child, and the remaining members of the clan. They all bow down to acknowledge their new leader.

Another Lotus Blossom

This leads us to the film’s problematic portrayal of Japanese women. As Bustle’s Olivia Truffaut-Wong has argued, the film perpetuates the Hollywood stereotype of fetishizing Asian women as being passive, submissive, and sexually subservient to white men. Miyu is the only speaking female character in the movie. Practically every other Japanese woman that appears on screen is a prostitute or a half-naked stripper. By the end of the film, Miyu has lost her brother and her independence to become wholly dependent on Nick.

When she first appears as a waitress at the Shiromatsu bar, she flirtatiously offers Nick a bottle of American beer. They meet a second time when Kiyoshi asks him to accompany her home. When they get there, she invites him to sleep with her – despite having only exchange a few words with him thus far (and thus proving Panetti’s words to be prophetic). Even though Kiyoshi insists that Nick should stay away from his sister – to prevent her from becoming a casualty during gang turf wars – he pursues her throughout the film.

In the middle of the film, we learn that Orochi was Miyu’s former lover. After praising her beauty, he physically assaults her for rebuffing his advances. He threatens to rape her – but ultimately decides to leave her alone. This dual set of associations – Asian men are violent and misogynistic; white men are noble and dependable protectors – is firmly embedded in many of Hollywood’s interracial pairings.

Another Orientalized Vision of Japan

Reviewers from The Daily Beast, AV Club, The Guardian, Consequence of Sound, The Hollywood Reporter, Variety, and Thrillist have all pointed out that the film has little interest in exploring the complexities of Japanese culture, or its historic setting. The film is set in an arresting time: a period when Japan was reshaping itself into a global economic powerhouse after the destruction of World War II. At the hands of Danish director Martin Zandvliet and American screenwriter Andrew Baldwin, the audience is left with little insight about Japan. Instead, they are bombarded with a familiar and empty set of visual cliches: yakuza members committing ultra-violent acts in black suits, kabuki theater, katanas, sake-drinking, koi fish tattoos, a ritualistic tea ceremony, seppuku, yubitsume (finger-chopping), sumo wrestling, etc.

The point is to ultimately present another (tired) vision of white male exceptionalism, Asian servitude, and an exoticized, tourist-level view of Japanese culture and history. In this regard, The Outsider has even less to offer than similarly problematic predecessors such as Lost in Translation (2003) or Memoirs of a Geisha (2005).

P.S. Netflix has a mixed record when it comes to Asian and Asian-American representation. Let them know what you think of this problematic film via Twitter (@netflix) or their customer service channels (if you are a subscriber).

-

OFFENDER: Netflix

CATEGORY OF OFFENSE: Self-Aggrandizement ( Whites are Central)

MEDIA TYPE: Movie

OFFENSE DATE: March 1, 2018