“To All the Boys I’ve Loved Before” Has a Divisive Premise

To All the Boys I’ve Loved Before, a Netflix adaptation of Korean-American author Jenny Han’s bestselling 2014 novel of the same name, has received generally favorable reviews from film critics, inspired numerous memes and Buzzfeed quizzes, and solicited a mixed reaction from the Asian American community. Like the book, the film revolves entirely around its teenage female protagonist’s love life – which sees her transition from being a hopelessly romantic and introverted daydreamer to being romantically entangled with many of the boys she covertly harbored feelings for after her secret stash of love letters are mailed out. While the cinematic adaptation of the novel involved a notable amount of racebending, the trailer made it evident that this made no difference when it comes to Asian American male representation.

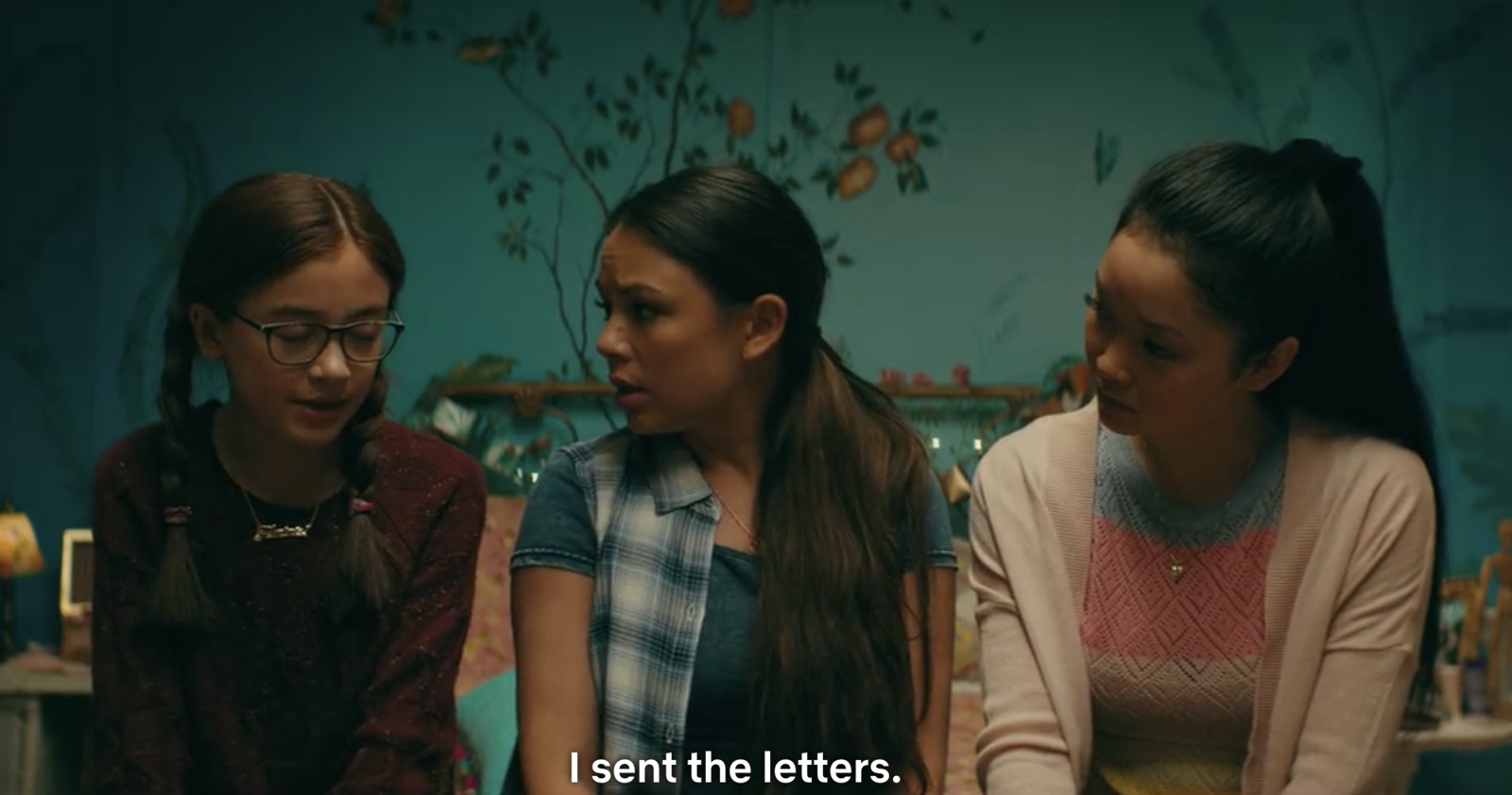

The Covey Girls: Kitty, Margot and Lara Jean.

The film has been rightly lauded for featuring an Asian-American actress (Lana Condor) in a leading role. The idea of having an Asian-American actress playing the leading role in a teenage romantic comedy film may not appear to be particularly groundbreaking, but one should note that such roles have rarely been offered to Asian-American actors. In 2013, Lucy Liu revealed that the role of the everyday, all-American girl-next-door had been out of reach for most of her career: “I wish people wouldn’t just see me as the Asian girl who beats everyone up, or the Asian girl with no emotion. People see Julia Roberts or Sandra Bullock in a romantic comedy, but not me.” In 2017, sociologist Nancy Wang Yuen noted that Hollywood casting directors had the impression that Asian actors were particularly ill-suited for the art of self-expression:

“I work with a lot of different people, and Asians are a challenge to cast because most casting directors feel as though they’re not very expressive. They’re very shut down in their emotions … If it’s a look thing for business where they come in they’re at a computer or if they’re like a scientist or something like that, they’ll do that; but if it’s something where they really have to act and get some kind of performance out of, it’s a challenge.”

The problem, however, lies in the film’s particular vision of a “progressive” and “post-racial” America and its own erasure of the Asian American community. Lara Jean Song Covey, the film’s protagonist, is a sixteen-year-old half-Korean, half-Caucasian girl. Condor is a Vietnamese-American, while the actresses playing her two sisters – Janel Parrish and Anna Cathcart – are half-Asian and half-Caucasian. Since their Korean mother is dead, the only father figure in their lives is Dr. Covey (John Corbett), a gynecologist. Their Korean identity is only alluded to via their nostalgia for their mother’s cooking and Lara Jean’s preference for an unspecified “Korean yogurt drink”. Apart from the Covey sisters, no other Asian or part-Asian character plays a significant role in the film.

Lara Jean’s Asian-American schoolmates are briefly featured as they make way for her first public appearance as Peter Kavinsky’s “girlfriend”.

When this particular social milieu is combined with Lara Jean’s primarily white love interests – the presumably white Lucas Krapf from the book was replaced by the black Lucas James in the film – you get a vision of suburban America where romantic couplings between Asian/part-Asian women and Caucasian men are seemingly inevitable. Since James promptly reveals that he is gay and the letter to “Kenny from camp” is returned (it was addressed to the camp where they met), Lara Jean spends most of the movie caught between her taboo feelings for boy-next-door Josh Sanderson (who happens to be her older sister’s ex-boyfriend) and her budding romance with lacrosse jock Peter Kavinsky. The movie’s ending hints that “John Ambrose from Model UN” will complicate Lara’s newfound relationship with Peter in a possible sequel.

Despite its post-racial milieu, the film regurgitates the Orientalist binary of the West as masculine and the East as feminine.

As Hanh Nguyen pointed out in an article on IndieWire, “it’s discouraging to see an Asian author perpetuate the narrative of only white men being attractive, and by exclusion, that Asian men are not.” When asked to address the criticism about the lack of an Asian-American love interest in the narrative, author Jenny Han revealed that she “shared that frustration of wanting to see more Asian-American men in media.” At the end of the day, however, she did not see herself as an agent for change: “For this, all I can say is this is the story that I wrote.”

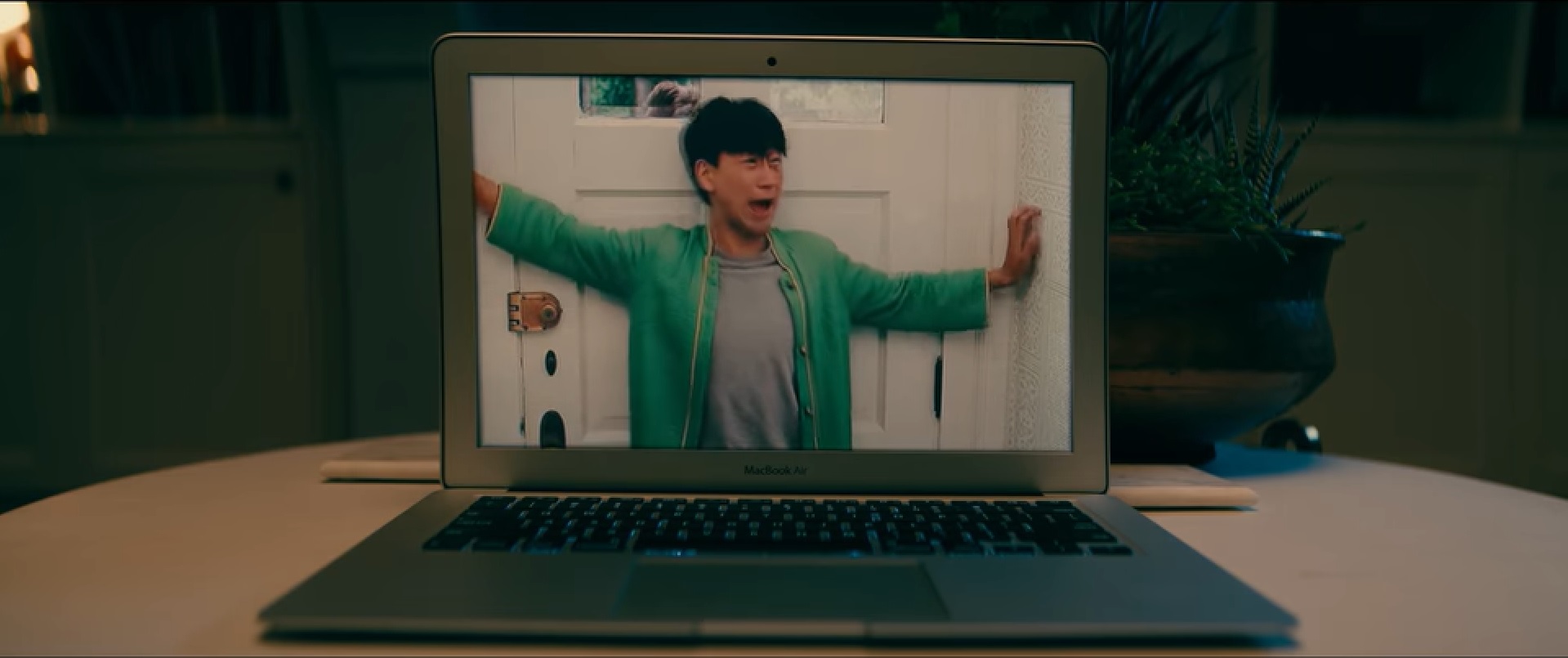

Long Duk Dong’s offensive antics make an appearance when Lara Jean watches “Sixteen Candles” with Peter and Kitty.

Thinkpieces in Plan A Magazine and Slate have also singled out a particular scene (which was not in the book) for being highly problematic. In the movie, Lara Jean is a big fan of Sixteen Candles (1984), presumably as a meta reference to how the film draws from John Hughes’ legacy of thoughtful cinematic depictions of small-town teenage life. She forces Peter Kavinsky to watch it with her and her younger sister Kitty, and the camera lingers on Long Duk Dong – the character that actress Molly Ringwald herself has acknowledged as being a “grotesque stereotype”:

Peter: I’m sorry. Isn’t this character – Long Dong Duk – like kinda racist?

Lara Jean: Not kind of, extremely racist.

Peter: So why do you like this movie?

Kitty: Why are you even asking that question? Hello, Jake Ryan!

Peter: I am way better looking than that guy.

Life imitates art mass-market paperback romance novels (a genre that is itself plagued with a dearth of diversity).

What are screenwriter Sofia Alvarez and director Susan Johnson attempting to achieve with this scene? It would appear that Lara Jean and Kitty are so far removed from anti-Asian racism in their comfortable, post-racial suburban milieu that they can easily dismiss “one of the most offensive Asian stereotypes Hollywood ever gave America”. Another way to interpret this scene, however, is as a form of unintended meta-commentary on To All the Boys I’ve Loved Before itself. Are present-day fans of the movie similarly dismissing concerns that Lara Jean’s singular romantic preference for her white peers may not simply be a desire for assimilation but a sign of internalized racism – simply because the movie endows the actor Noah Centineo with the heartthrob status which has been historically reserved for Caucasian actors?

“Diversity” applies to Lara Jean’s social life, but not to her romantic imagination.

In Romance and the “Yellow Peril”, a provocative analysis of Hollywood representations of interracial relationships, Gina Marchetti warned that “the means to challenge Hollywood’s hegemony over the representation of race and ethnicity remain elusive […] Access to the industry also exists, but entrance demands a tacit agreement to assimilate, at least to a certain degree, with the dominant culture.” In this case, the progress achieved by TATBILB (an Asian-American lead actress who has agency over her romantic decisions and is not exoticized by her racial identity) comes with a leading protagonist that only has whiteness on her mind when looking for love.

As of July 2018, Netflix has phased out user-submitted reviews. You can voice your concerns by contacting them on Twitter (@netflix), calling them at 800-852-6334, or by submitting a user review on Metacritic.

-

OFFENDER: Netflix

CATEGORY OF OFFENSE: Gender ( Asian males are Omitted)

MEDIA TYPE: Movie

OFFENSE DATE: August 1, 2018