The Problems with Asian Representation in HBO’s Westworld

In the original 1973 film, the Westworld theme park sidestepped questions of race by eliminating people of color from the narrative, as well as hyper-realistic robots modeled after people of color. The android hosts that inhabited the three futuristic amusement parks in the film – Westworld (the American Old West), Medievalworld (medieval Europe), and Romanworld (Pompeii) were engineered to resemble white gunslingers, prostitutes, sheriffs, cowboys, knights, and maids. The wealthy guests that visited the park to indulge their appetites for sex and murder and the technicians responsible for overseeing the park were mostly white men.

Logan, a privileged and uninhibited guest, casually claims an East Asian male host and a black female host for himself upon arriving at Westworld.

The ongoing HBO TV serialization created by Jonathan Nolan and Lisa Joy is far more ambitious in scope and ends up biting more than it can chew when it comes to the problem of race. Westworld departs from its predecessor’s lily white ensemble by (1) including amusement parks with hosts modeled after people of color; and (2) alluding to the presence of a multiracial future America that exists outside of the park. The overarching plot (the robot hosts eventually rebel against their lot of being passive outlets for endless human cruelty) remains, but the capacity of the hosts’ quest for self-determination and equality to serve as a metaphor for the struggle against sexism, racism, classism, and other forms of marginalization in America’s past and present has been amplified. As several TV critics have noted, however, Nolan and Joy have a mixed record when it comes to tapping into the full potential of this metaphor – especially when it comes to Asians and Asian Americans.

The Hosts

The premise of HBO’s Westworld inevitably reflects the racist and sexist status quo of today (and much of human history). The guests that inflict much of the abuse on the hosts in Westworld are, for the most part, wealthy white men. The masterminds behind the conceptualization and execution of this sadistic theme park are also white men. There are white male hosts (e.g. Teddy Flood) who are repeatedly brutalized and murdered by the park’s guests, but most of the physical and sexual violence depicted on screen is inflicted on the female hosts and non-white male hosts.

Ganbei! Maeve (Thandie Newton), a host programmed to play the part of a bordello madam, entertains two mainland Chinese hosts (who appear once, serving only to establish that the park has an international clientele).

As The New Yorker’s Aaron Bady argued in December 2016, the robot rebellion is, inevitably, “an imperfect metaphor for the quest for human equality” since robots are destined to be human creations – and due to the narrative complications introduced by the show’s writers. Without the robot rebellion plot, however, the show would become unquestionably indefensible. (As it is, there are already concerns that the show focuses more on the shock value of seeing the hosts being tortured and violated than the potentially redemptive significance of seeing them mounting a hard-won rebellion). The audience would then simply become stand-ins for the unethical guests and creators of this cynical amusement park, free to act upon their outsized superiority complex on the helpless, dehumanized and perpetually victimized hosts.

Torture porn?: hosts modeled after white women and people of color endure disproportionate levels of physical and sexual violence.

For better or for worse, Westworld’s writers decided to fully lean into the idea of the robot rebellion serving as a metaphor for the plight for a historically marginalized group of people with the show’s Native American hosts in episode 8 of season 2 (“Kiksuya”). In episode four of the same season (“The Riddle of the Sphinx”), a similar creative decision is made when the show revealed that the Westworld theme park actually attined a level of historical accuracy that involved Chinese railway workers (who had previously been out of sight):

“Part of the show is playing with the tropes of Westerns. The full story of all the different people who went into building the West … [the park] is a picture of a picture of a picture that’s as much about how we reinvent history to suit the people telling those histories as much as history itself. For me, I’ve always been fascinated by tales of the Chinese railroad and the workers and the conditions of the workers who built the railroad. America is built on the labors of the oppressed. The story in the first season, we had these hosts, and we focused on the female characters, you put them through hell, again and again; at what point do they revolt? Much the same way, you see these hosts forced to play this role of Chinese railway workers, and they decided to rebel against the people forcing them to work to the bone.”

Lisa Joy, Entertainment Weekly

Role reversal: the Westworld park’s Chinese hosts stage a murderous revolt in episode 4 of season 2 (“The Riddle of the Sphinx”)

The Orientalist Fantasies of Shogunworld and Rajworld

Unfortunately, Westworld never “focuses” very long on its Asian hosts’ aspirations towards a greater consciousness (or on combating the erasure of Asians from popular representations of the Old West). The audience never gets a chance to empathize with the Asian-American hosts they way they do with the park’s African-American hosts (chiefly Maeve and Bernard), white hosts (Dolores, Teddy, and Clementine), Native American hosts (Akecheta) or Latin American hosts (Hector). The Man in Black (Ed Harris) simply stumbles upon the aftermath of the Chinese railway workers’ “rebellion”, makes a few comments, and then moves on with his quest.

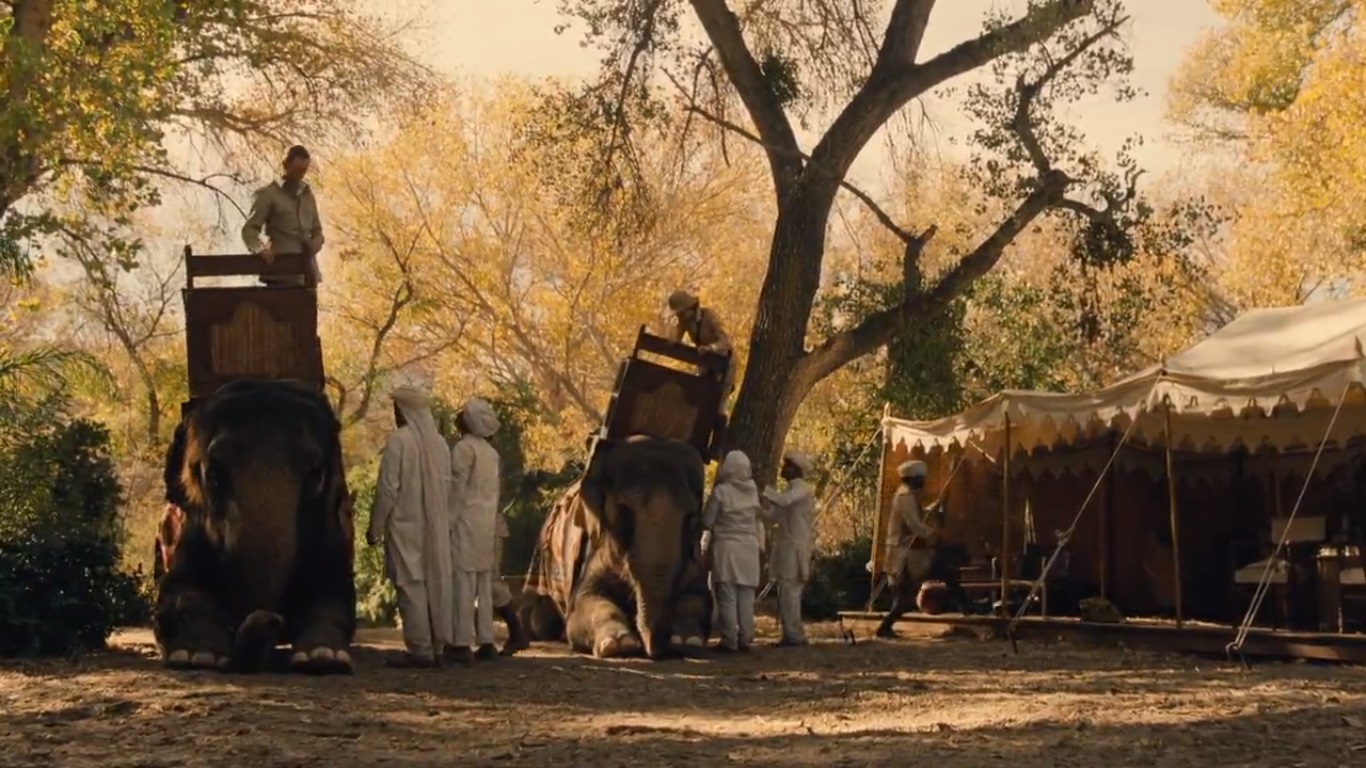

White guests ride on elephants and hunt Bengal tigers in The Raj, which first appears in episode 3 of season 2 (“Virtù e Fortuna”)

Westworld devotes more screen time and character development to the Asian hosts that inhabit Shogunworld (a recreation of feudal-era Japan) and The Raj (British colonial India). On the surface, the show signals its self-awareness about the nature of these colonial fantasies and the tropes and stereotypes they contain. After concerns were raised about the very real possibility of cultural appropriation, Nolan and Joy carefully expressed their reverence for Akira Kurosawa’s samurai films and the lengths they went – an elaborate set, costumes, and Japanese actors speaking in an archaic poetic register – to create an “authentic” homage to them:

“The reason we went with the shogun, Imperial Japanese motif for that world is in large part because of the beautiful relationship you had between the golden age Westerns and the golden age samurai films. As soon as Akira Kurosawa would make a film, it would get remade with cowboys. The idea that those stories worked in two very distinct genres and languages, and the relationship between those genres, to me was irresistible as an homage to how Kurosawa was responsible for some of the greatest Westerns of all time.”

-Christopher Nolan, The Hollywood Reporter

If you look past the exquisite cinematography and meta-commentary about recycled tropes (the hosts and narratives that play out in Shogunworld were basically repurposed from Westworld), the narrative that plays out in episode 5 of season 2 (“Akane No Mai”) unfortunately lives up to the promise that Shogunworld would please guests who find Westworld “too tame”. Maeve and company are greeted by the sight of numerous dead bodies (“Beautiful way to watch the sunrise … glistening off the intestines of the recently mutilated”), and then get entangled in a violent conflict that involves a sadistic Shogun, his army of ninjas and samurais, and fiercely independent geishas. After being abducted and mutilated, geisha dancer Sakura is murdered by the psychopathic and misogynistic Shogun (“When the Shogun asks for meat, he does not wish to hear the story of a cow”). In return, Sakura’s protector Akane (Rinko Kikuchi) slices off the top of his head with a concealed dagger.

“The Shogun said he wanted to make me more beautiful.”

An All-Too-Familiar Vision of the Future

Westworld sheds little light on the nature of the technologically advanced world that exists outside of its sprawling amusements parks. The workplace dramas and corporate intrigue narratives that unfold take place in the park’s management facility, where a predominantly black and white vision of multiculturalism predominates.

The brief presence of a Chinese naval officer in episode 1 of season 2 (“Journey into Night”) suggests that the Westworld amusement park is located on an island in the South China Sea.

The staff that populates Delos Incorporated, the nebulous conglomerate that owns and operates the amusement parks, are too preoccupied with the question of whether the hosts have enough sentience to be treated as humans to overtly address any of the racism or sexism inbuilt into the amusement parks that surround them. As other critics have pointed out, however, the show itself perpetuates racist and sexist tropes that work beyond the confines of its conceit.

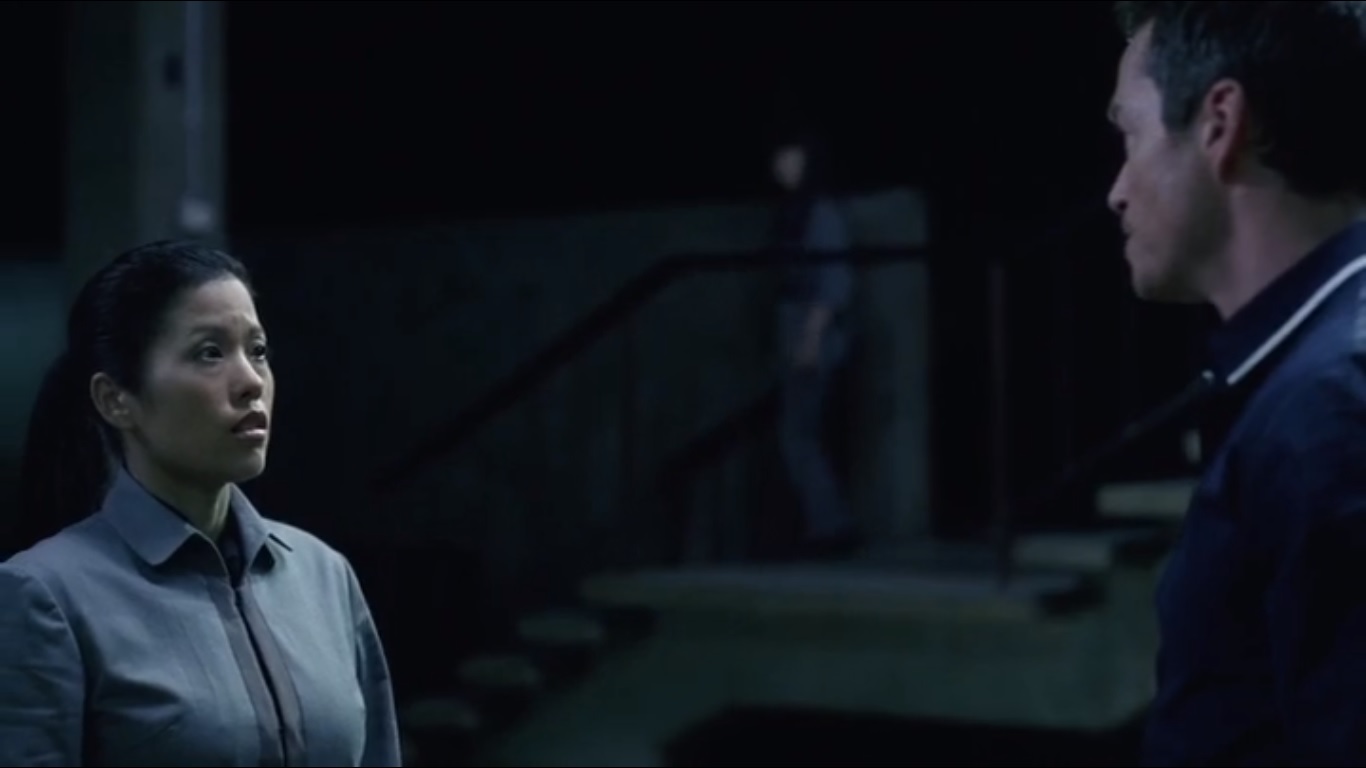

Lee Sizemore, Westworld’s hackneyed narrative director, takes out his anger on an East Asian female subordinate (Nanrisa Lee) for the size of a Native American host’s nose.

Felix Lutz (Leonardo Nam), a Livestock Management division employee and the show’s primary Asian recurring actor, exemplifies how Westworld can critique existing racial stereotypes while also perpetuating them. One one hand, he gets to call out his obnoxious coworker Sylvester for assuming that he can speak Japanese: “I’m from Hong Kong, asshole.” Felix’s character arc as a shy, empathetic, and ambitious technician who aspires to become a coder is not overtly offensive, but his unwillingness to defend himself against his colleague’s bullying (e.g. “Personality testing should have weeded you out in the embryo”) perpetuates stereotypes of Asian meekness in the American workplace:

Sylvester: What the fuck, ding-dong? You dress her up now? It’s becoming like a fuckin’ hentai thing with you now?

Felix: No, I just … I just …

Sylvester: You’re fuckin’ obsessed! You know I didn’t turn you in for your fuck-up before. Cause we’re friends. But that was obviously a bad call. You know, the next thing I know, you’re gonna be wearing her dress. Whispering sweet nothings in her ears. Fuck this! I’m telling QA. I’m doing this for your own good.

Sylvester berates Felix in a racialized manner for treating Maeve with some compassion.

Even if one finds a way to rationalize away all the Asian stereotypes that find their way into Westworld, it’s impossible to deny that its Asian characters (whether host or human) are given the same chance to be as nuanced, dynamic, or compelling as their black, white, or Native American counterparts. Viewers might find some fleeting satisfaction in Felix’s mini empowerment narrative or the brief scene of revolting Chinese railway worker hosts, but their presence is mostly incidental to the overarching plot. At the end of the day, Felix’s main role so far has been to aid Maeve’s empowerment narrative. One can only hope that he gains more significance in season 3.

Present but uninvolved: an “unawakened” East Asian host remains oblivious to the rebellion that Dolores catalyzes right in front of him.

-

OFFENDER: HBO

CATEGORY OF OFFENSE: Denigration ( Reinforces Stereotypes)

MEDIA TYPE: TV Show

OFFENSE DATE: January 1, 2019