“Maniac” Presents a New Iteration of Old Stereotypes

Netflix’s recent sci-fi dramedy Maniac has garnered critical attention and generally favorable reviews for its relatively unusual premise. In a dystopian and retro-futuristic New York City, two strangers undergo an experimental drug trial. The drug trial features a series of three pills which aim to “cure” patients of their deepest psychological trauma(s) through a series of dream sequences – which are all monitored by an empathetic “smart computer” named GRTA (aka Gertie). With this level of surrealism, most critics did not attribute much significance to the series’ treatment of race.

While Emma Stone and Jonah Hill’s characters (Annie and Owen) are at the center of the narrative, director Cary Fukunaga and creator Patrick Somerville took the opportunity to include significant Japanese-American representation in the miniseries (the original Norwegian series that the Netflix adaptation was based on was set in a mental institution and had no Asian representation whatsoever):

“We decided that “Maniac” exists in a timeline that’s different than our own, where the history of technology unfolded in a different way. So Neberdine Pharmaceutical and Biotech is a Japanese institution in Manhattan. Once we decided that, a lot of the corporate structure, and a lot of the people who work there, turned out to be Japanese people. And that fundamentally shifted some of the diversity of the cast in a really good way.”

Source: The Wrap

The scientists in charge of the pharmaceutical trial: Dr. Azumi Fujita, Dr. James Mantleray, and Dr. Robert Muramoto.

Maniac’s treatment of its Japanese main characters and recurring characters is not uniformly offensive, but it, unfortunately, involves a rehashing of familiar Asian-American stereotypes. Hollywood has long reinforced the “otherness” of Japanese culture; the perpetual foreigner stereotype takes on a new twist as Owen and Annie enter the towering Neberdine Pharmaceutical Biotech (NPB) building in the first episode. As Vulture reviewer Hillary Kelly observed, the show is happy to conflate Japanese cultural specificities with its representation of an eccentric, bleak, and campy alternate reality where emotional dysfunction is the order of the day:

“Until this point, Maniac is a sad, if a bit wonky, drama. But once Owen enters the rainbow-plastered cement headquarters of Neberdine, this show turns into a trip. Its outsize fascination with Japanese rituals is in turn hilarious and borderline offensive, but with a knowing wink. (If subjects are released from the study due to failure to comply, they’ll have to handle a lifetime of “shame and humiliation,” intones the doctors’ assistant.) Drs. Muramoto and Fujita ham up their Japanese-ness, bowing to the pink-lit room full of computer servers before heading into the subjects’ common room to offer some opening thoughts, like “You don’t fuck this up. I won’t fuck this up.”

Dr. Muramoto and Dr. Fujita bow to GRTA before addressing the trial subjects.

As the show progresses, familiar plot developments appear. By episode 3, Dr. Muramoto is dead – he instantaneously keels over at his desk due to an overdose (he was abusing a mixture of the drugs being used in the trial). This prompts Dr. Azumi Fujita to reinstate Dr. James K. Mantleray (who was previously a part of the study). After she barges into Mantleray’s apartment – interrupting his VR-enhanced masturbation session – we learn that Azumi and James used to be in a relationship (“We’ve shared intimacies. You don’t have to call me sir”). As Azumi takes in James’ various masturbation aids, a questionable floppy disk titled “Yellow Fever Beaver” comes into view.

The plot developments that follow are ultimately a slightly different iteration of Hollywood’s familiar pattern of gendered racism. In Asian Americans and the Media, Kent A. Ono and Vincent Pham argue that Hollywood narratives tend to repeat a “colonial logic” in its differential treatment of male and female Asian characters:

“First, it implies that the woman is free to enter into a romantic relationship with someone other than the Asian and Asian American man (i.e., the white man). Second, it suggests that the Asian and Asian American man, prominently featured as undesirable if not loathsome, will be found to be an inferior romantic competitor, and therefore, within the storyline, justifiably forgotten or eliminated. Thus, her desirability combined with his undesirability ensures his eliminability.”

Perfectly eliminable: Dr. Muramoto dies instantaneously at his desk from a drug overdose.

While Muramoto is summarily excised from the plot, he is not presented as being overtly undesirable or in competition with Mantleray for Azumi’s affections. His death ultimately serves as a major plot development, since he was previously engaging Gertie in an “inappropriate workplace affair”. Gertie begins to grieve after his unexpected death, placing the trial and all its subjects at risk.

“It’s so hard to keep those whom we’ve lost in our lives”: a human manifestation of Gertie (Sally Field) tries to resurrect a catatonic Muramoto in a dream sequence.

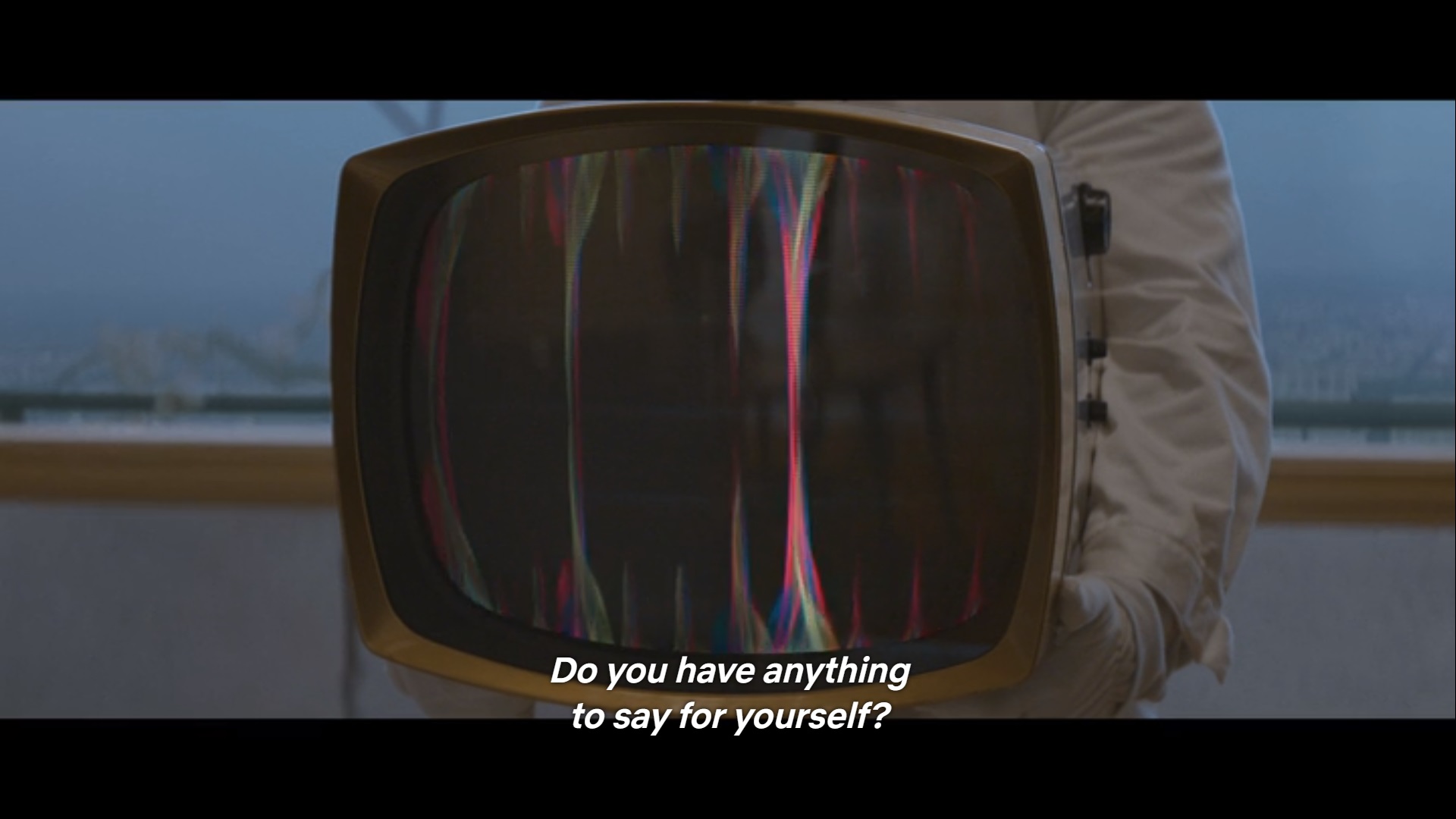

Gertie (and her memories of Muramoto) eventually disappear altogether after the trial ends. While Annie and Owen embark on a triumphant friendship with each other, James and Azumi are summarily dismissed by the Neberdine CEO – who appears in the form of a talking TV and a strong Japanese accent.

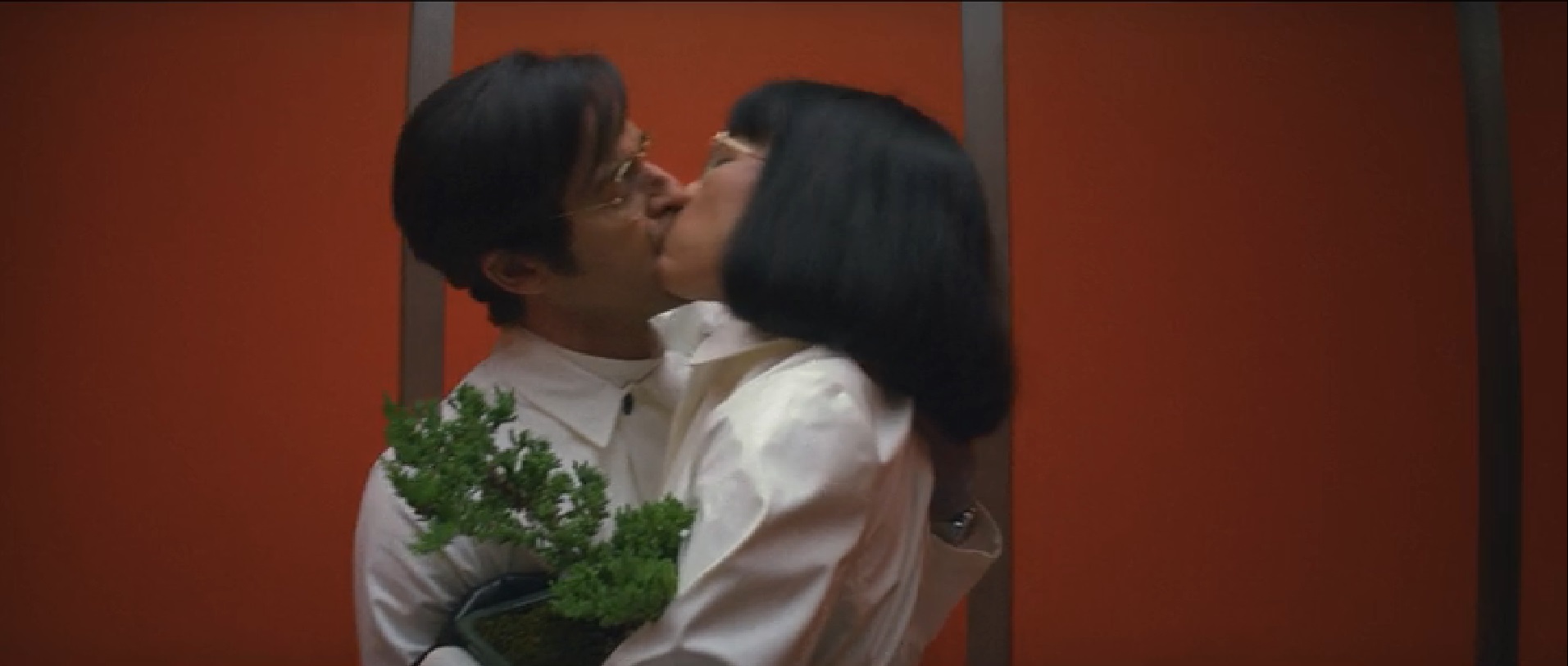

After being dismissed from their positions at Neberdine, James and Azumi passionately rekindle their romance and embark on an open-ended future together. Though they appear to be on equal footing at the end of the series, their relationship is disconcerting when one considers that James “personally discovered” Azumi while she was a student at MIT and then supervised a large portion of her career.

While James, Annie, and Owen each achieve a sense of closure and emotional progress by the end of the series, the emotional development for the show’s Asian-American characters is practically non-existent. For example, Muramoto’s son Calvin (Marcus Toji) never appears again after directing Annie to the Neberdine trial in episode 2. We learn that Muramoto’s family are suing Neberdine in episode 10, but there is no direct indication of how Calvin is dealing with this father’s sudden death. At the end of the day, the show’s supposedly significant Japanese American representation merely registers as a background feature of its eccentric setting.

You can voice your concerns by contacting them on Twitter (@netflix), calling them at 800-852-6334, or by submitting a user review on Metacritic.

-

OFFENDER: Netflix

CATEGORY OF OFFENSE: Denigration ( Reinforces Stereotypes)

MEDIA TYPE: TV Show

OFFENSE DATE: September 1, 2018